Working with the sun, the light and the wind

(April 2024) | In the projects you have worked on at RPBW, your top priority has always been to tailor your design approach to the building’s function and to protect the site and its surroundings throughout the construction process. How do you achieve these goals in practice?

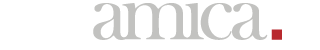

In recent years, I’ve worked on a variety of residential and non-residential projects in locations such as New York, San Francisco and Lisbon. Our architectural approach involves an integrated design process that spans multiple disciplines. In an apartment and hotel project in San Francisco, for example, we designed a façade system that incorporates solar tubes to harness sunlight for hot water production. This involved collaborating with a team of engineers and façade manufacturers to create and test prototypes, ensuring they met our specifications and the building’s needs as effectively as possible. In Lisbon, we’re finally completing a long-running housing project in an area close to the Tagus River. It’s been fascinating to observe how the design principles we value – such as the interaction between indoor and outdoor spaces, integration with the city and the local community, the creation of semi-private inner courtyards, and engagement with the site’s natural elements – are also those that are most relevant to the challenges we face today. Improving air quality, ensuring natural ventilation and focusing on thermal comfort are all aspects that we’ve prioritised and which remain crucial to our work.

What new green technologies do you expect will be adopted in the architecture of the future?

I don’t believe we need to invent new types of buildings or ways of living in the future. Instead, we should focus on improving what we already know and, most importantly, putting this knowledge into practice. When it comes to future living spaces, I firmly believe in the idea that homes – along with the surrounding outdoor spaces – need to be protected. This is why, in our Lisbon project, we chose to include a variety of outdoor living areas like terraces, courtyards and winter gardens, each offering different levels of privacy. Winter gardens and terraces are private spaces that allow residents to live in close proximity to the outdoor environment. We also added a raised garden above street level that can be accessed from the apartments, creating a sheltered, communal space for all the building’s residents. Last but not least, the project includes a public park that can be used by everyone. Future building designs should initially aim for carbon-neutral structures, then evolve towards carbon zero, taking account of each project’s unique function and location. While there’s no one-size-fits-all solution, adopting an integrated design approach is vital as it ensures that residential buildings are more resilient and adaptable to different climates, weather conditions and maintenance needs.

Another challenge is to renovate existing buildings sustainably so as to improve their energy performance. What solutions did you adopt for the restyling of Monte Rosa 91, the former headquarters of Il Sole 24 Ore?

The Monte Rosa 91 project is situated in what used to be the headquarters of Il Sole 24 Ore, constructed in 2000 on the site of an older industrial complex.

After approximately 15 years, the building required a comprehensive redesign. The new client, AXA, envisioned a multi-tenant building with shared spaces not only for the people working there but also for the local community and the broader city population.

This project addresses the very topical issue of transforming existing buildings for public use. A key goal of this renovation was to cultivate a collective space that opens up to the street and its surroundings, achieved by retaining the original layout of an internal landscape and enhancing the transparency towards the street.

The decision to prioritize transparency enhances the sense of urbanity, subtly capturing the complexity of layered views. The U-shaped building has a horizontal perspective and houses several business units, augmenting the flexibility of the original structure in both the working and communal spaces.

Does that mean that enhancing permeability is one of the main features of this renovation project?

The building’s transparency plays a crucial role in maintaining an overall vision. From Via Monte Rosa, the view isn’t limited to a single plane but extends in depth, allowing onlookers to see through the large glass walls to an inner square and a green hill beyond. We worked hard to make the inner square a lively, inclusive space where events could be held outside of working hours. We also devoted a lot of attention to the greenery concept in both the square and the new hillside development, and added a restaurant, a kindergarten and a gym.

We also made a lot of effort to adapt the building to the new energy-saving challenges. Since it was opened in June 2023, the building has experienced a big revival, and this year there are plans to open the hill area, which will be called the Parco della Luce (“Park of Light”).

What’s the latest project you have been working on?

For the past two years, I’ve been working on Milan Polytechnic’s new Bovisa Campus, situated in the city’s Goccia neighbourhood. The first step in the redevelopment of the area was the repurposing of the two large gasometers that stand as key features in the Goccia landscape.

Gasometer 1 is being transformed into the Smart City Innovation hub, while Gasometer 2 will become the Sport Factory, equipped with gyms, a swimming pool and sports facilities. The Campus Nord, designed by the Renzo Piano Building Workshop, will subsequently be constructed around the two gasometers, surrounded by greenery. This part of the campus is envisioned as a hub of knowledge and innovation, integrating academic activities with university-related services and fostering connections with the business sector and the city’s wider community. The masterplan is organised around a main pedestrian walkway positioned north of the gasometers, with orthogonal paths branching out from it. Vehicular accessibility is minimised and kept to the periphery. Parking will be intentionally limited to promote the use of the many existing and future public transport services available to the area. In keeping with this shared vision, the Milan City Council has plans to establish a new Civic Schools complex near the campus and to revitalise the extensive urban woodland in the Goccia area.

How did you envision the layout and function of the buildings?

The buildings have a flexible, cohesive design and consist of rectangular structures facing onto the park and the tree-lined streets. Although they share similar floor plans, they each have distinct characteristics and volumetric layouts according to their specific functions. The campus has three primary functions: classrooms for teaching, start-up incubators and university residences capable of accommodating 500 students. There is also a large underground conference hall with a seating capacity of 450, along with a large food factory, situated within a historic Officine del Gas building. The buildings dedicated to start-ups are envisioned as spaces that foster incubation and acceleration in an open, welcoming environment. They are designed to promote networking among graduates, companies, experts, institutions and investors. Inside, resources and knowledge will be shared to accelerate the pace of technological progress and to provide economic and strategic benefits. At street level, the Campus Nord buildings are designed to be open and permeable, facilitating urban interaction, gatherings and socialisation. The building masses appear to float above the ground level, with interior spaces spread across three functional floors – extending to four in the residential buildings – and making extensive use of open-plan layouts to encourage shared activities.

What sustainable strategies have you adopted?

The shed roofs, which in the past were used to screen light in industrial settings, now serve as supports for solar panels for converting light into energy. These panels are placed side by side like petals to create a single large roof which appears to float at a height of about 16 metres above the ground, unifying the project while supplying all the energy required for operation. The Campus project is designed to harness energy from the sun, the earth and the air. Large photovoltaic roofs will be used to produce energy, geothermal systems to exchange heat efficiently with the ground, and a district power plant equipped with an electrolyser to store surplus energy produced during the summer in the form of hydrogen. The campus will be both zero energy and zero carbon, achieving energy independence without any atmospheric CO2 emissions during its lifetime.

All buildings on the campus will be constructed primarily from wood, a natural, lightweight, recyclable and above all renewable material. The trees that will be planted on the campus are expected to replenish the timber mass used in the construction of the buildings within 30 years.

Ceramic played an important role in your residential project in Lisbon. What do you consider to be the technical and aesthetic qualities of this material?

Working with ceramic tile on the façade of our residential project in Lisbon gave me the opportunity to learn about the material’s many strengths and advantages. Foremost among these is its resistance to weathering, impact and corrosion, making it an excellent choice for both indoor and outdoor applications and ensuring a long lifetime with minimal maintenance.

Moreover, ceramic tiles contribute to the thermal and acoustic efficiency of buildings due to their insulation properties, while the ease with which they can be adapted to different architectural forms and configurations means they can be easily installed on a wide variety of surfaces. Ceramic tiles are often made from natural and recyclable materials, making them an environmentally friendly choice for sustainable architectural projects.

Last but not least, ceramic tiles offer unparalleled versatility and come in a wide range of colours, finishes, shapes and sizes, allowing for endless creative and customised design possibilities. In short, they offer a unique combination of strength, durability, sustainability and flexibility. In our project in Lisbon where they are used on the building facades, they demonstrate an exceptional ability to play with light, creating varying hues depending on the weather conditions and bringing the building to life.